The Six Key Attributes of More Biodiverse Cities

Advertisement

The following six city scenarios are proposed based on visions that recognize the complexity and dynamism of urban systems and shed light on concrete strategies to improve the link between spaces, human inhabitants, and non-human inhabitants. This reminds us of the hybrid nature of cities, the role of built infrastructure and technology as mediators of society-nature relationships, the importance of recognizing local capacities, and each context's biological and cultural capital. These visions are complementary and can operate jointly. Still, they are based on different ways of understanding the urban matrix in space and time, drawing from design, ecology, and territorial planning approaches. While catastrophic visions of the future of megacities prevail, it is important to think more positively about the future of these cities to bring about positive change. Each vision highlights the narratives and paradigms that must be adopted to move towards new ways of integrating the biological, social, and technological dimensions and, thus, achieve cities that contribute to biodiversity conservation, development, and human well-being.

1. The Metahuman

The metahuman city starts with the question of what or who inhabits the urban landscape and, therefore, reflects on the coexistence of multiple life forms. It overcomes the vision of the “user” or “client” and understands that human well-being is closely linked to the health of other living beings. This “decentering” of the human being as the sole representative of life that governs the city’s destinies invites us to rethink the relationship of human populations with other life forms and how the design and management of the urban matrix influences this relationship. How do we reconcile the needs of human comfort with those of a tree’s roots in a public space? Why are temporary hotels important for pollinators? How can the noise produced by a city disturb the communication of birds? How can we address the challenges associated with coexistence between humans and other species in relation, for example, to conflicts with the emergence of zoonotic diseases?

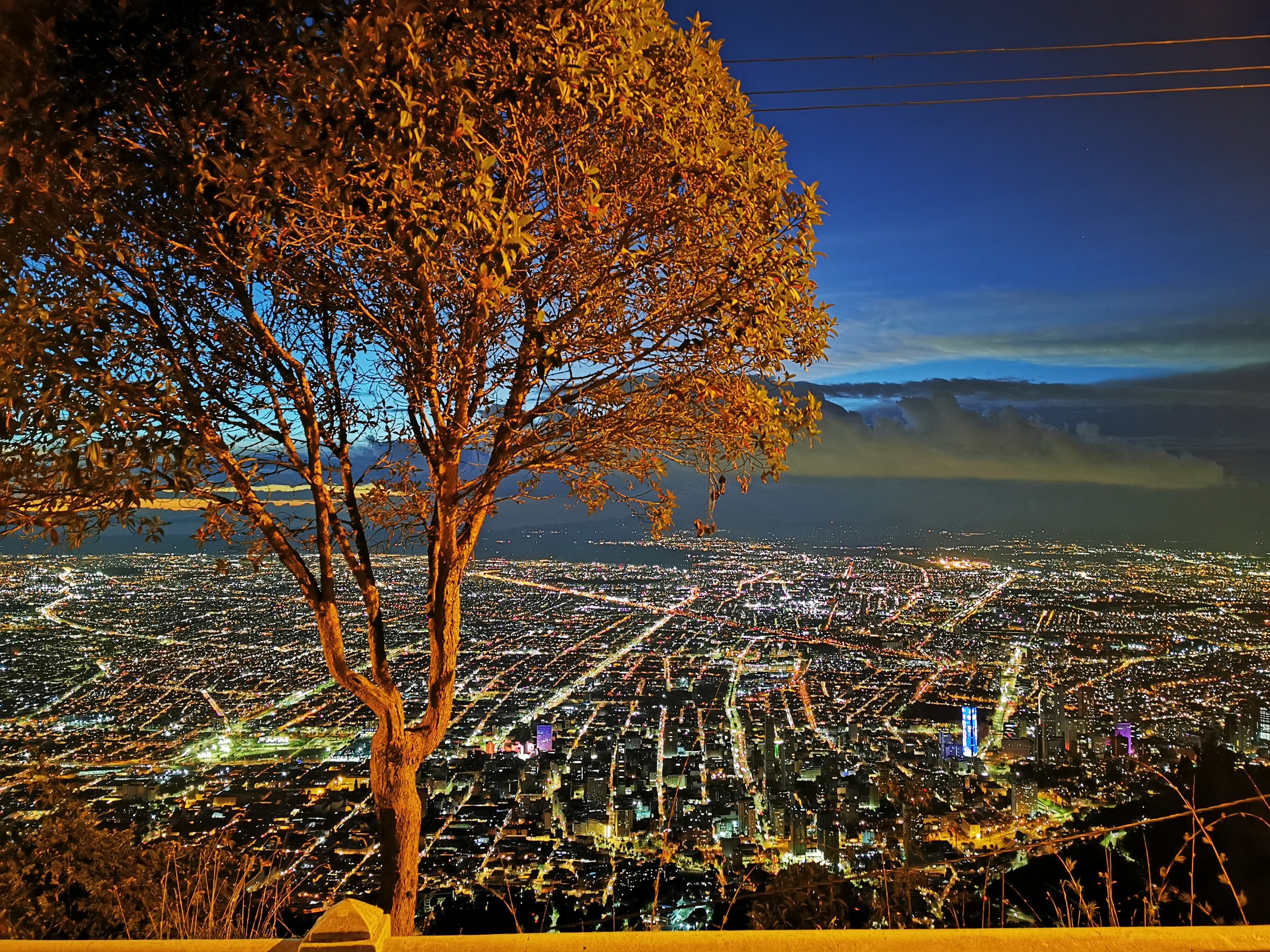

An endemic tree standing on top of the eastern hill of the megacity of Bogota. Photo: Andrés Ibañez Gutierrez

Attributes of the Metahuman City

It maximizes positive interactions between different life forms, considering the services and disservices offered by nature in urban contexts.

It explores new methods for identifying non-human requirements related to, for example, habitat availability or conditions to ensure the mobility of certain species.

It recognizes natural cycles and the behavior of a variety of life forms in relation to these cycles.

It integrates life at different scales of urban planning and management.

The world’s biodiversity represents a unique opportunity and a huge challenge to take advantage of the natural and cultural capitals of the territory in urban environments. How should urban centers generate habitat for birds and design adequate infrastructure for visitors who practice bird watching? How can the great diversity of orchids, bromeliads, lichens, and bryophytes be used to enrich urban infrastructure? These questions suggest that urban planners, architects, and other designers should incorporate knowledge generated by other disciplines - such as biology, ecology, or social sciences - and work together on innovative design proposals that promote healthy spaces for diverse life forms. Another area of particular interest for the future of the metahuman city is the use of new information technologies and the articulation between various sectors of society.

Advertisement

2. The Wild

Historically, the biotic dimension of urban environmental quality has mainly been related to two parameters: the number of square meters of green areas, and the number of individual planted trees. While these indicators facilitate the understanding of the presence of biodiverse settings in a city and usually contribute to organizing and managing the benefits they can provide, they are limited in accounting for the potential that this set of natural or semi-natural urban pieces can offer to the quality of life and the sustainability of urban space. While urban growth is skyrocketing in many regions, increasing the quantity of “megacities”, divergent trends have been observed in areas of economic decline where “wild” ecosystems have begun to appear in urban-industrial areas. This illustrates the ecological and social potential of urban environments and spontaneous vegetation to increase green areas’ biodiversity and reduce costs in their management.

Attributes of the Wild City

Nature reclaims its place in the patio of a residential complex in Chapinero, Bogotá. Photo: Andrés Ibañez Gutierrez

It builds a vision of the relationship between biodiversity and urban quality of living, beyond green area indicators and the number of individual trees planted.

It seeks to maximize interactions between social and ecological systems.

It prefers the complexity of the relationships among various life forms over the simplicity of the individual.

It reduces human maintenance through self-regulation and adaptation.

It allows for spontaneity and values it as a form of resilience.

Natural ecosystems express themselves in diverse and complex ways. Incorporating them into city planning requires advancement in management tools that measure effectiveness and estimate the cost-benefit of unusual strategies such as the intentional abandonment of certain areas or the promotion of natural succession. In practice, disciplines like restoration ecology, biology, architecture, and urban planning should work hand in hand to include these types of actions in managing the urban matrix.

3. The (Un)finished

The last page of the High Line’s history was written against all odds by biodiversity. As calls grew for the total demolition of what was left standing of the elevated railway, nature reclaimed the underutilized space, and plants began to grow spontaneously, creating habitats for birds, insects, and other non-humanized life. Hundreds of people came together for the common purpose of caring for that new space. It is now an elevated park recognized worldwide for completely changing the face of Manhattan’s west side by creating wild places for recreation, contemplation, citizen gathering, urban agriculture, artistic and cultural events.

Advertisement

Local ecosystems spontaneously emerge on top of a brown roof in the wetland ecosystems of western Bogota. Photo: Andrés Ibañez Gutierrez

Attributes of the (Un)finished City

It recognizes cities as dynamic socio-ecosystems in constant change.

It contemplates several future scenarios considering the opportunities for the collective production of the urban habitat.

It designs and builds in uncertainty, even in the absence of accurate information.

It prioritizes adaptability in urban design processes.

It enables the participation of communities and citizens in the city’s construction. It formulates strategic interventions at key places to trigger new processes in the future.

It values urban planning actions that strengthen flexibility and adaptability over time.

It values spontaneous citizen initiatives.

In the developing world, the (un)finished city is a common dynamic that has existed since the emergence of urban settlements. More than 20 per cent of a megacity like Bogotá has an informal origin, with settlements characterized by inadequate or absent infrastructure in high-risk areas and limited access to essential public services. Given that the process of formalizing these neighborhoods is complex, slow, and tedious, thousands of citizen groups come together to intervene in public spaces with works that seek to improve the living standards and strengthen citizen identity through participatory activities that involve the entire community.

To walk through these neighborhoods is to see a mosaic of unfinished citizen interventions in constant transformation: graffiti, tactical urbanism, ecological restoration, public space, parks, markets, and urban agriculture. Likewise, planting food and ornamental plants in urban spaces is common in the informal areas of Bogotá, such as Ciudad Bolívar. This area has become an enclave of urban farmers, seed and food preservers, and leading defenders of biodiversity and local nature since many of its inhabitants come from rural territories. In the (un)finished city, the collective conception and production of the urban habitat are valued based on recognizing the specific conditions of each territory, promoting planning as a dynamic process facilitates the inclusion of the perceptions, interests, and expectations that communities have about the city’s development. This includes the different ways in which communities relate to nature, which is contrary to the top-down approach.

4. The Overlapping

The possibility of buildings being crowned with large parks or green and biodiverse surfaces is not the only option, nor the best. Still, there are various ways to overlap natural spaces and built space to multiply activities and functionalities according to each place’s needs and spatial characteristics.

Architect James Ramsey set in motion an idea as far-fetched as it was brilliant: to build the world’s first underground park, the Low Line, in an abandoned and underutilized urban space in Manhattan. The key to the project’s success was enabling photosynthesis. This was achieved by incorporating optical devices in the urban space to capture, reflect and redirect solar radiation into the underground space.

Advertisement

Andean bamboo crowns the roof of a high-rise residential building in Bogota. Photo: Andrés Ibañez Gutierrez

Attributes of the Overlapping City

It assigns a particular site several uses and functions simultaneously.

It builds spatial relationships in three dimensions, not two.

It integrates human activities into areas destined for biodiversity conservation.

It incorporates compatible uses into protected areas, which reduces conflicts.

It accepts and promotes biodiversity conservation outside protected areas.

It operates like a forest, as different things happen at various levels and win-win interactions are built, generating co-benefits.

It promotes and constructs buildings and inert infrastructure with green roofs, green walls and other elevated elements and creates natural corridors.

In cities, avenues connect distant places of origin and destination but fracture relations of proximity and pedestrian connectivity. The overlapping city suggests that roads can be covered by living surfaces that attract biodiversity and articulate the urban divide caused by road axes for pedestrians. The Bicentennial Park in Bogotá, built on an underground section of El Dorado Avenue, is a starting point in the strategy of efficient use of space. It can be replicated in other parts of the city and urban centers in Colombia. Likewise, in Medellin, another Colombian city, the UVAs (Articulated Life Units) are an excellent example of the overlapping city, as recreational spaces and biodiversity enclaves were created on pieces of functional city infrastructure, such as water storage tanks.

These cases demonstrate that, contrary to popular belief, if we know how to take advantage of urban space and better understand the needs of non-human organisms, cities with high occupancy density rates still have space available for biodiversity. Interventions that make more efficient land use in cities can significantly and positively impact biodiversity and socio-economic development. This brings nature back into the built environment, reduces the infrastructure footprint, frees up land for nature, and generates new economic value.

5. The Bio-Performative

Many modern cities are asynchronous with natural phenomena and are designed merely for visual appreciation. This creates a disconnection between inhabitants and the life experience of biological cycles, the types of light the sun produces throughout the day, the seasons, weather changes, atmospheric phenomena, plant phenology, and water cycle dynamics. We have for long ignored how synchrony with natural rhythms provides plenty of design alternatives to make our cities move livable and functional.

The term bio-performative is used here in the same sense as “performative architecture”, which refers to how one or more environmental events determine a space or place; in this case, events caused by non-human life forms and natural cycles.

Advertisement

Attributes of the Bio-Performative City

It connects and communicates urban human inhabitants with natural cycles, life processes, and, in general, environmental phenomena, thus promoting the incorporation of such phenomena in the design of public spaces and built structures.

It incorporates the circadian cycles of human beings and the biological cycles of non-human beings into urban planning and design processes.

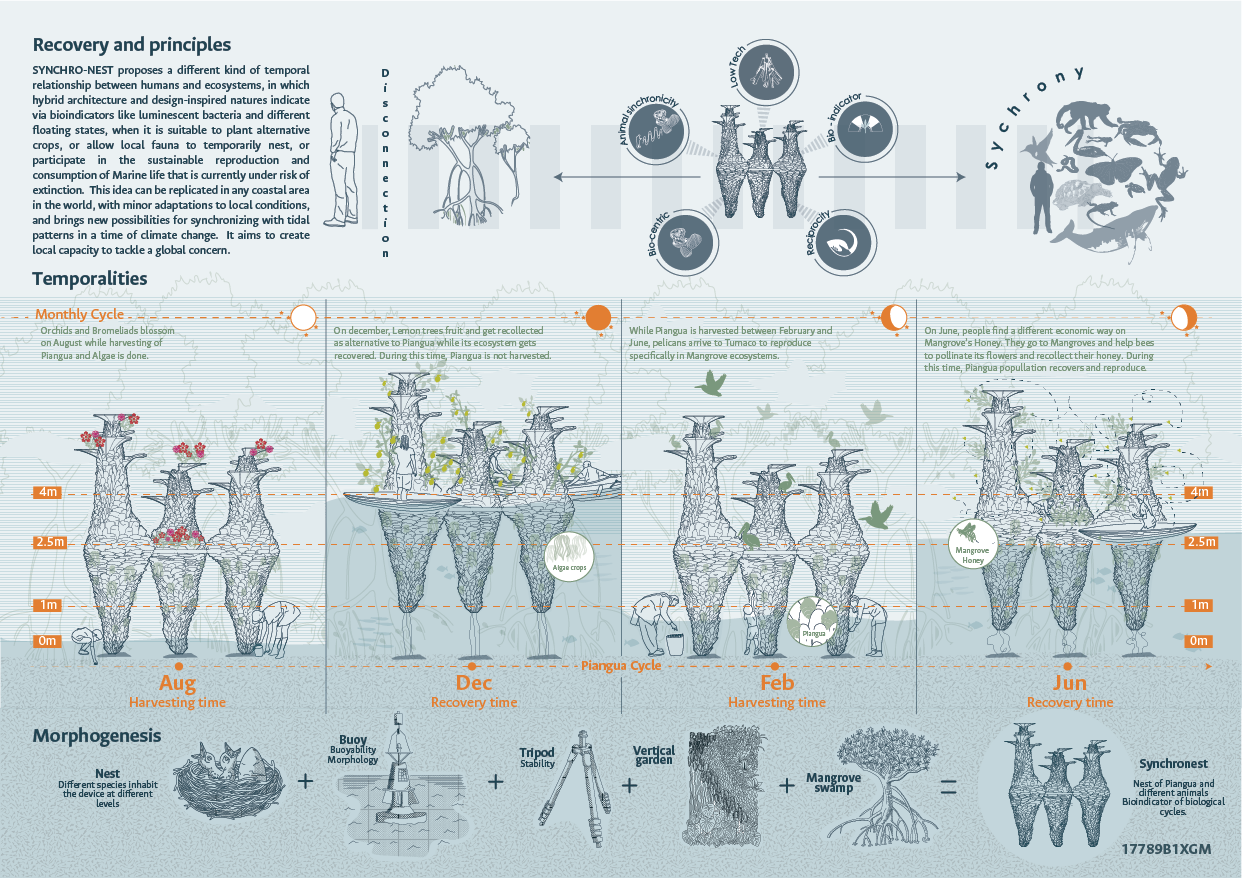

Synchro-nest is a piece of landscape architecture proposed by a research team at National University of Colombia. This nature-based solution adapts to the different seasonal changes and water levels throughout the year in the mangrove ecosystem of Tumaco in the southern pacific coast of Colombia. Design team leader: Andrés Ibañez

How do we incorporate the potential of biodiversity in the connection of people with their immediate environment in cities of the present and future? Some conditions define the environmental behavior of the territory and characterize aesthetic experiences. Cities and architecture must be a sounding board that amplifies these experiences, for example, the sound of animals, the management of water and rain as an integral element of the inhabited space, or the incorporation of natural light. The bio-performative city understands the biological and climatic changes that occur over time and in each territory and seeks to incorporate them into the design of infrastructure and public space.

6. THE BIOMIMETIC

Although biomimicry is a recent trend, it is estimated that nature-inspired design will produce at least 30 per cent of economic growth in several technology sectors globally, including construction and architecture. At the city scale, biomimicry has explored how some characteristics of natural systems can guide strategies to improve the resilience of urban infrastructures. Among these strategies, the inclusion of diversity in different dimensions and scales of the system, the strengthening of multifunctional design and urban-regional relationships, and the management of local biodiversity from the ecosystem-based adaptation approach stand out.

Attribute of the Biomimetic City

It integrates strategies inspired by the functioning of organisms and biological systems.

It uses climate adaptation strategies of local species and ecosystems.

It prioritizes principles and patterns of operation over form.

It replaces traditional technologies with solutions based on how nature works.

It creates an environment of innovation based on the study and local biodiversity research.

Advertisement

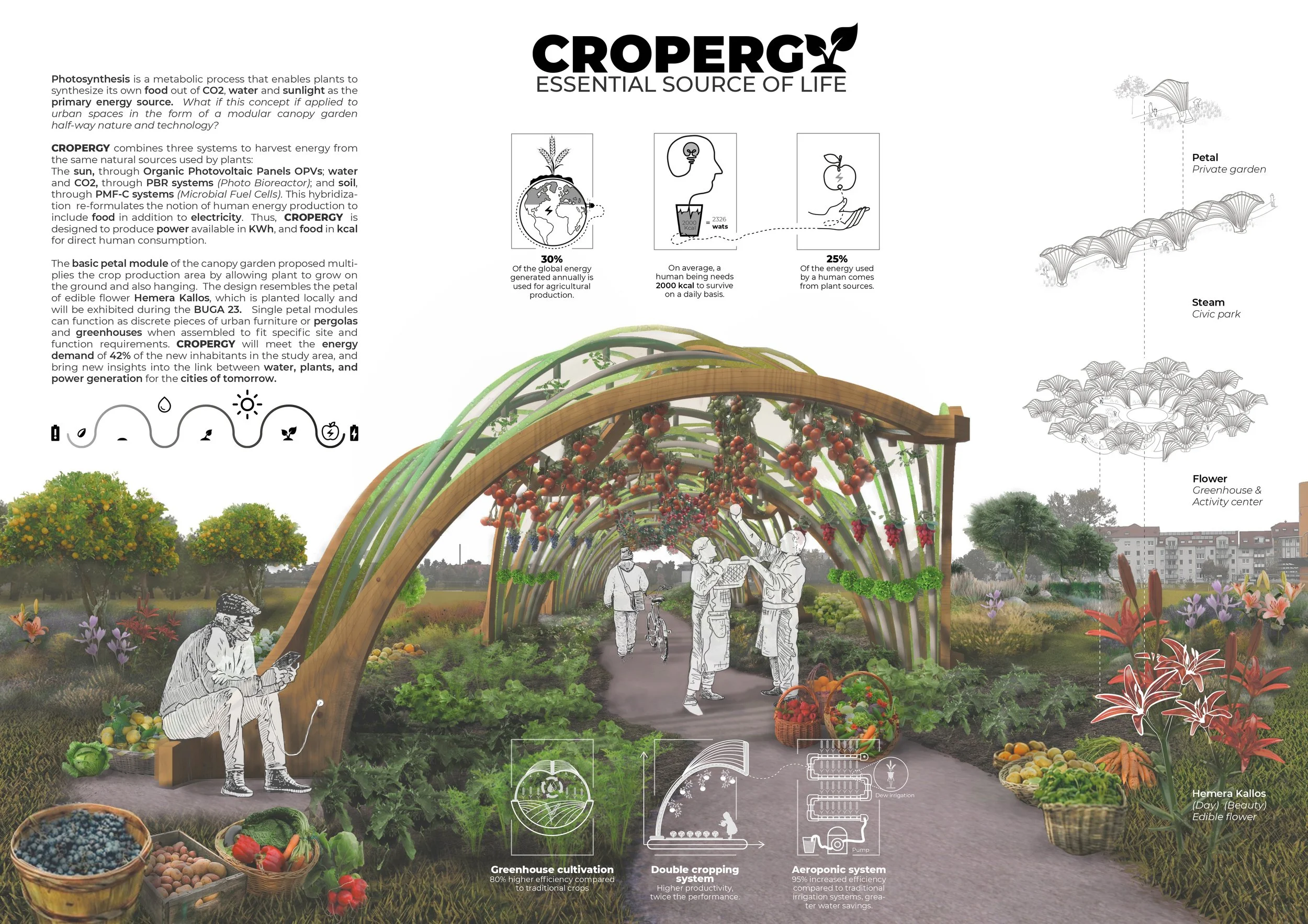

Cropergy is a modular piece of public infrastructure that produces food and clean energy inspired by the metabolism found in plants proposed by a research team at National University of Colombia. Design team leader: Andrés Ibañez

Possible Futures

Although cities offer opportunities as global centers of transformative innovation, catastrophic visions of their future still prevail, hindering the implementation of plans and policies for creating more positive scenarios, both locally and globally. The visions presented in this article seek to contribute to more positive discussions about the future of urban environments and thus motivate actions and inspire processes that will generate transformative changes in the years to come. For example, the vision of an overlapping city increases the possibilities for relationships among citizens and between citizens and nature within the urban matrix; likewise, the vision of an (un)finished city recognizes city-building as a complex and emerging phenomenon resulting from the interaction among multiple socio-ecological factors. Increasingly, governments and academia are adopting approaches that promote green and inclusive cities through concepts such as sustainable urban development, urban ecosystem services, green infrastructure, or nature-based solutions. However, it is necessary to strengthen languages and approaches that transcend the instrumental conception of nature and human activities as drivers of negative transformations towards socio-ecological models that recognize the multidimensionality of society-nature relationships in the context of each territory. In recent years, new methodological frameworks have been developed such as nature-based thinking, which suggest transcending the use of nature as an isolated solution to specific urban challenges towards regenerative and biophilic cities that provide spaces for biodiversity and ecological processes.

Advertisement

Andrés Ibañez Gutierrez is the Director, School of Architecture and Urban design, Universidad Nacional de Colombia raibanezg@unal.edu.co

About the Biodiverse Cities 2030 book project:

When this book project started, we encouraged all contributors to reflect on the question: What are the transformations needed to reach BiodiverCities by 2030? With this invitation in mind, in August 2021, over 80 scholars, practitioners, leaders, promoters, and visionary individuals from 44 cities were convened to reflect on how cities can restore their relationship with nature.

You can visit the book project website here.

The complete book in PDF version is available at no cost here.